This piece originally ran on the Impact Malaria website.

Malaria in pregnancy is a major health threat to the lives of pregnant women, fetuses, and infants. Pregnant women are particularly at risk from malaria as their immunity against the disease declines during pregnancy, increasing the risk of anemia, severe illness, and death. For the unborn child, maternal malaria can cause premature delivery, low birth weight, and death. In areas that are malaria endemic or have moderate to high transmission of the malaria parasite, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a three-part package of interventions for preventing and controlling malaria and its effects during pregnancy. This includes the promotion and use of insecticide-treated bed nets, the administration of intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp), and prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment of malaria.

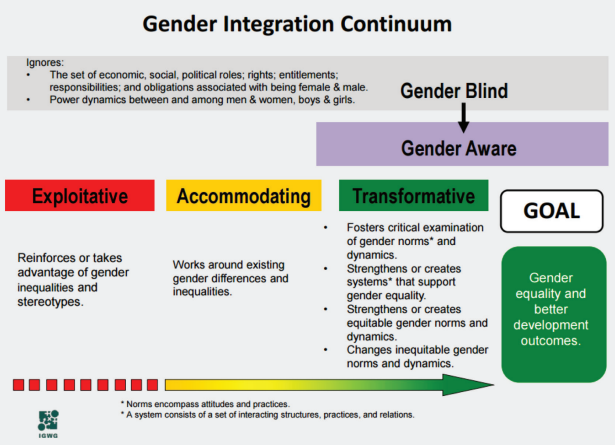

PMI Impact Malaria supports 11 partner countries to strengthen and expand malaria in pregnancy services by collaborating with the Ministries of Health, National Malaria Programs, reproductive programs, and maternal and child health programs. While evidence links gender and socio-cultural barriers to reduced uptake of reproductive and maternal health services in general, information is limited about their link to early entry into antenatal care and retention in care throughout pregnancy, as well as their link to the uptake. In Camarões and Kenya, we collaborated with country partners to conduct assessments to understand gender-related barriers to accessing and adhering to malaria in pregnancy services.

Ahead of International Women’s Day, we spoke with PMI Impact Malaria’s senior technical advisor and resident expert on gender and malaria, Elizabeth Arlotti-Parish (right), to learn more about the assessments, why adopting a gender approach is a valuable component of malaria service delivery, and how the findings are informing project activity (the interview has been edited for clarity):

What was the impetus for this assessment?

Early in the project, the PMI Impact Malaria Kenya and Cameroon country teams noted that women were not using malaria in pregnancy services or sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets*, and the teams did not understand why they were not adhering to these lifesaving, preventive measures. They thought that gender norms and power dynamics within the couple, family, and community, might be a root cause but they wanted to undertake an assessment to be certain. Knowing the root cause could then inform necessary changes to increase education of and access to these lifesaving tools. In both countries, the teams conducted a gender analysis to explore what issues acted as barriers to malaria in pregnancy services.

*Insecticide-treated bed nets are a lifesaving, preventive tool recommended by the World Health Organization to be used over beds. This prevents malaria-carrying mosquitoes from biting while the user is sleeping. These are one tool in the malaria prevention toolbox.

Why is it important to apply a gender approach to improve the quality of malaria service delivery?

Research in other health areas has shown that the technical competency of health providers is only one reason that motivates clients to seek care. If a client receives quality services but is not treated kindly, or with empathy or compassion, other assessments have shown that she is unlikely to return and may even tell her friends of her experience and influence them not to seek care. Oftentimes this mistreatment she experiences is due to gender biases on the part of the health care worker, or the gender of the health worker him or herself. We also know that understanding the benefits of care is not the only motivation for clients to seek care. A client may know the benefits of attending antenatal care or taking anti-malarial drugs, but she may face gender-related barriers in her family or her community that impede her from care-seeking. If we do not consider how gender influences care-seeking, or the provision of care, these barriers will remain, and women will not get the care they need.

What were the main findings from the qualitative assessment?

We learned that in both Cameroon and Kenya, male partners and mothers-in-laws often control women’s decision-making about attending early antenatal care, and in fact many of the factors that would often be cited to be the preferences of the woman were instead the preference of someone else that influenced her decision. For example, we heard that many women preferred traditional medicine providers over health facility providers, but with some probing it came out that this was because the husbands and mothers-in-laws preferred this, and in some cases the mothers-in-law were traditional providers themselves.

We also learned that, even if a woman delayed seeking antenatal care, once she started going, she would continue (and the decision-makers in her household would support that), if she felt like she was treated respectfully by the nurse or other provider. Not one woman or other respondent mentioned needing the provider to be clinically competent, but many indicated that a woman would not return if she was not treated with respect.

Finally, when it came to intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy (IPTp)*, we heard form many women that they did not like the medicine because it made them feel sick. That experience was expected, but what was surprising is that we clearly heard from the respondents is that health providers did not take their concerns seriously and thought that by continuing to explain the importance of the medicine and watching women take it, that the problem would be solved. Instead, women felt that being forced to sit in front of a provider to take the medicine was coercive and made them not want to return to care.

* IPTp, a public health intervention aimed at preventing malaria in pregnant women, is a series of antimalarial medicine provided to women at routine visits to keep them safe from malaria infection during their pregnancy.

What are the key messages from this assessment?

Engage male partners and mothers-in-law in meaningful ways. Invest in helping providers to communicate with respect and compassion (and help them to understand that this matters just as much if not more than clinical competency). Take women seriously when they voice their concerns. Even if we can’t do anything about the side effects of IPTp pills, we can acknowledge women’s discomfort and respond with empathy, which makes them more likely to take the advice that is given, and to return to care.

(See the infographic below for this summary)

What problems might these findings solve to help communities prevent and treat malaria?

We can train providers, but if women do not seek care, malaria rates will continue to rise. Understanding the gender-related barriers that women face in seeking care, and understanding how health providers can effectively encourage continuation of care, will help us create effective interventions to help women get the care they need for malaria prevention and treatment.

Though not a shift that resulted from these studies, the best programmatic example we have of gender integration tied to results is in Mali, where PMI Impact Malaria invited the National Malaria Program (PNLP) to the team gender training. That motivated the PNLP to request that PMI Impact Malaria develop a gender module for the national malaria in pregnancy training, which has now been used with hundreds of providers.

Once a woman does begin care, decision-making power shifts [from social influencers] to the provider. A woman is likely to continue care, and practice other recommended behaviors such as IPTp use and sleeping under a long-lasting insecticidal net, if the provider treats her with respect, acknowledges and validates her concerns, and helps her to develop strategies to address them.

(Excerpt from PMI Impact Malaria Kenya assessment report)

PMI Impact Malaria is funded and technically assisted by the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) and is led by Population Services International (PSI) in partnership with Jhpiego, MCD Global Health, and the Malaria Elimination Initiative (MEI) at the University of California, San Francisco.