By: Susannah Gibbs, Technical Writer for Public Health Research, PSI; Lucinda Macaringue, Quality Assurance Manager, PSI Mozambique; and Paul Bouanchaud, Senior Research Advisor, PSI

The emerging global availability of effective COVID-19 vaccines has inspired a great deal of excitement. In Mozambique, vaccination of health workers began in March, and the country expects to have received more than 2 million doses by May. But the work to protect populations from COVID-19 doesn’t end with the development and delivery of clinically effective vaccines. A vaccine will only protect a population if enough people are willing to get it—and vaccine hesitancy poses a serious threat to achieving population-level protection against COVID-19.

At PSI, we’re conducting rapid research to understand vaccine hesitancy and to incorporate consumer voices into vaccine communication and distribution strategies. Our research indicates that vaccine hesitancy can change rapidly, and in Mozambique it appears to have increased just as supplies of the COVID-19 vaccine have started to arrive in the country. Governments, communities and NGO partners can build from these insights to foster vaccine confidence and combat misinformation.

We’ve tracked trends in vaccine hesitancy in Mozambique using panel survey data collected at three-month intervals since September 2020. The most recent round of data collection concluded in March 2021 and gives us nearly real-time information about current attitudes on the COVID-19 vaccine and how views in our sample have changed since the pandemic’s start. We will caveat that the sample likely skews wealthier than the general Mozambican population because the survey was administered by phone. Nevertheless, these findings provide emerging insights to guide strategies for increasing vaccine acceptance.

Vaccine Hesitancy in Mozambique: What the Research Says

Among our findings:

- Overall, people remain highly concerned about COVID-19. More than 90 percent of participants at each time point (and 97 percent in the last round of data collection) believed that COVID-19 was very dangerous.

- The perceived threat of COVID-19 has not translated into widespread readiness for the vaccine. We first asked about vaccine hesitancy in September 2020, before the approval of any COVID-19 vaccine. At that time, only 37 percent of people found the COVID-19 vaccine acceptable, saying that they would definitely get it, while the remainder expressed some level of hesitancy. Three months later, as the first healthcare workers were starting to receive their shot, or jab, in the US and the UK, acceptability of the vaccine rose to 44 percent in the sample. When we asked again in March, as shipments of the vaccine began to arrive in Mozambique, hesitancy had increased, and only 29 percent said that they would definitely get the vaccine.

- We’re seeing geographic variations: These trends were similar across provinces, but the overall level of acceptability varied substantially, ranging from 20 percent in Maputo City to 37 percent in Inhambane by March 2021. This geographic variation in levels of hesitancy may require tailored community efforts to address specific concerns about the vaccine.

- Attitudes can shift rapidly over time and much of the information available across countries may not reflect current conditions: Vaccine acceptance in low- and middle-income countries should not be taken for granted, and concerns about safety may cause rapid changes in views. Estimates of vaccine acceptability across countries vary. One study presenting data collected in June 2020 in 19 countries estimated levels of vaccine acceptability ranging from 55 percent in Russia to 89 percent in China. A report from Africa CDC that includes data collected in August through December 2020 from 15 countries in Africa describes vaccine acceptability levels ranging from 59 percent in the DRC to 94 percent in Ethiopia.

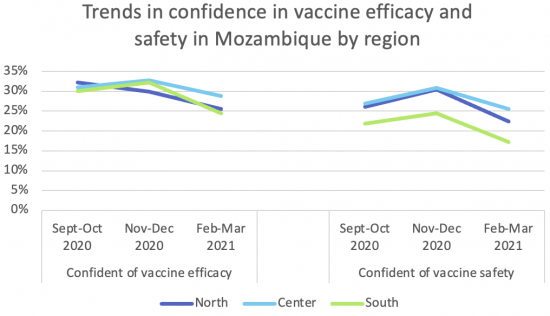

- We found that confidence in the efficacy and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine were on an increasing trend between September and December 2020, but by March 2021 confidence had declined across all regions: As vaccine distribution efforts ramp up in Mozambique, it’s critical to understand and address concerns about the vaccine. Concerns about effectiveness and safety are widespread across demographic groups. In the most recent round of data, 61 percent were very worried about the safety of the vaccine, and 58 percent were very worried that the vaccine is not effective.

- Reassuringly, we found no declines in trust across various sources of information: Trust in doctors remains particularly high, with 77 percent of people indicating a lot of confidence in them. Medical professionals may prove valuable allies in communicating information about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine.

Looking Ahead

Misinformation may be at the root of some vaccine hesitancy and can be spread rapidly through social media. In its COVID-19 Vaccine Development and Access Strategy, the Africa CDC has underscored the need for widespread community-engaged programs to address misinformation and encourage vaccine uptake. According to Lucinda Macaringue, PSI Mozambique’s Quality Assurance Manager, vaccine hesitancy also worsened in Mozambique after media reports about side effects of the AstraZeneca vaccine. “People are afraid of side effects,” Macaringue said. “But looking at the information that came, even people that before were considering vaccination started to hesitate.”

At PSI, our focus on consumer-powered healthcare shapes how we think about social and behavior change innovations to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Consumer voices guide the way. It’s also key to ensure that people who want the vaccine have positive experiences when they go to get it—barriers such as disorganized delivery and confusion about eligibility could lead to an increase in negative attitudes.

Using insights from these data, we can work with our partners in Mozambique (and beyond) to find the optimal trusted communication channels and identify populations that would most benefit from tailored social and behavior change messaging to decrease vaccine hesitancy. And we can continue to strengthen our approaches to collecting rapid and responsive data to support government, community and NGO partners in their work to address vaccine hesitancy.

There’s more

Certainly, the private sector has its challenges. From unreliable service reporting to inconsistency in adhering to national vaccination schedules, how can we get ahead of these gaps in priming the private sector to support COVID-19 vaccine delivery?

Read More